Could bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) hold the key to fighting bacterial infections and antimicrobial resistance, or even help treating non-infectious diseases such as cancer?

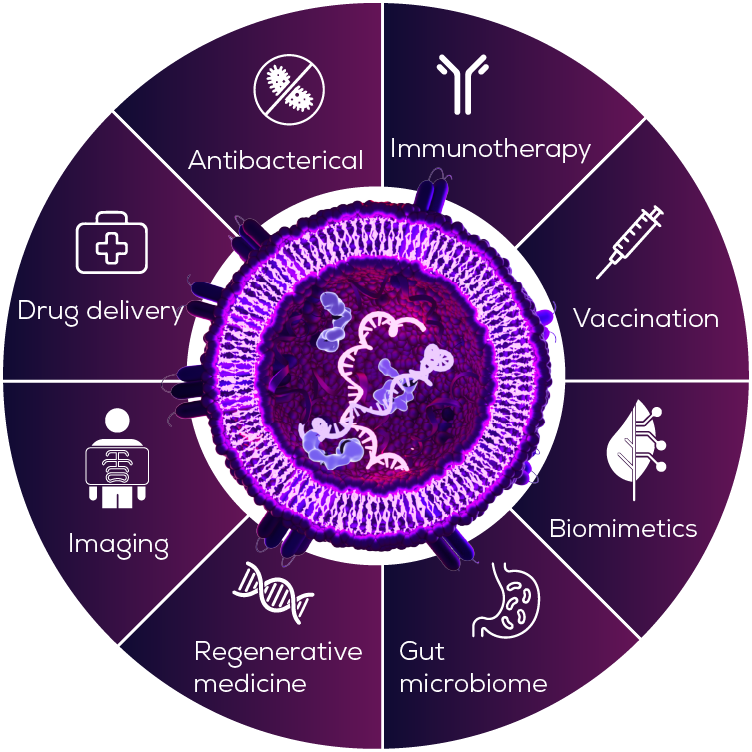

As we learn more about BEVs, their therapeutic potential is becoming increasingly clear – from vaccine adjuvants and drug delivery vehicles, to a whole range of other therapeutic applications (Figure 1). As it turns out, the very properties that make BEVs a dangerous part of the bacterial arsenal, may also make them effective medicine candidates.

Prevention is better than cure: OMVs as vaccine components

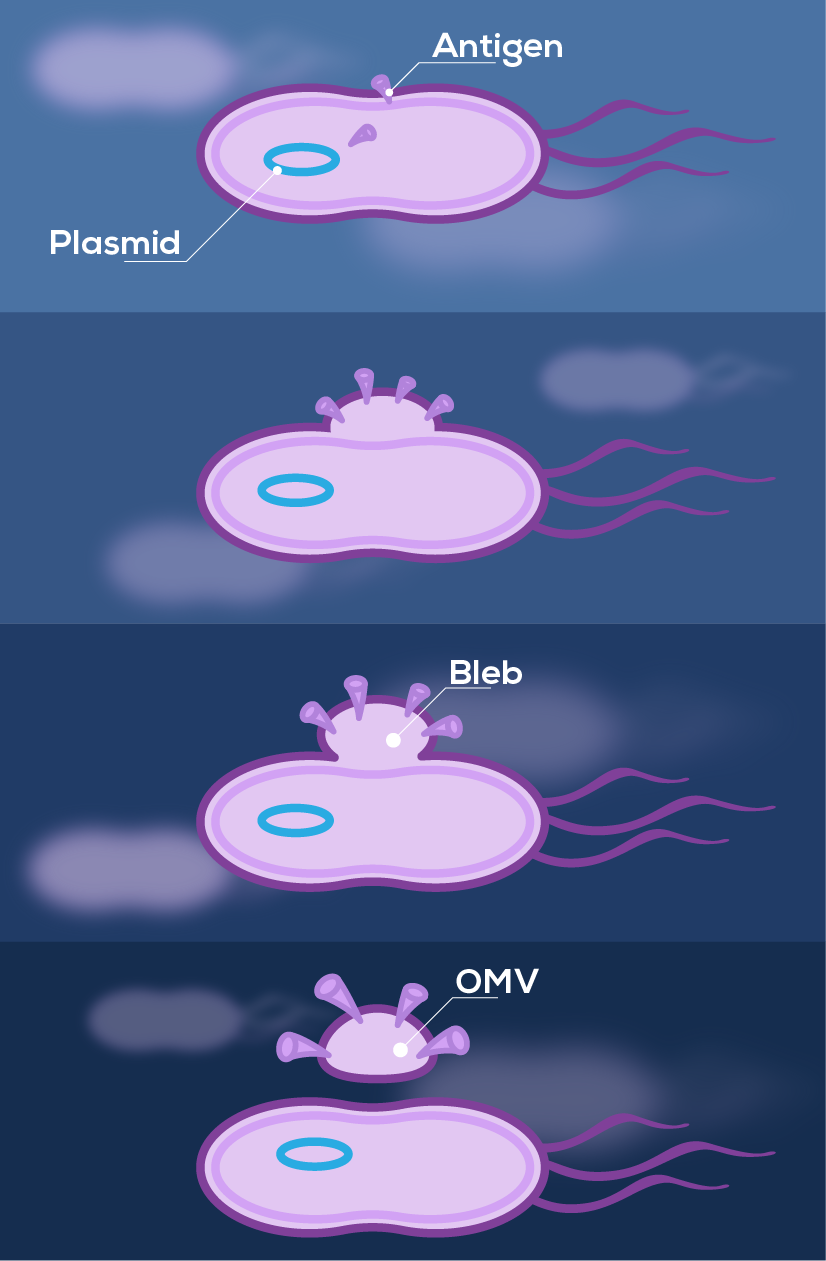

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) are a particular subtype of BEVs, produced by blebbing from gram-negative bacteria (Figure 2). They were first used in vaccine clinical trials in the late 1980s to combat outbreaks of meningococcal disease1,2. At the time, most meningococcal serotypes had effective vaccines based on their polysaccharide capsules, yet serogroup B polysaccharide was not a viable vaccine candidate and these bacteria continued to cause outbreaks of meningitis and septicaemia. OMVs were trialled as an alternative vaccine antigen, since they carry membrane proteins such as PorA that can trigger an immune response. These early OMV-based vaccines demonstrated good safety and efficacy, albeit in a strain specific manner2.

Building on this early OMV foundation, vaccines containing multiple components—including a mixture of recombinant protein antigens and OMVs—have now been developed. These vaccines offer broad-spectrum immunity against most meningococcal B strains, as well as some cross-protection against other serogroups3.

Importantly, the use of OMVs in vaccine development is not limited to targeting the bacteria they originate from or even to bacterial pathogens in general. Their dual capabilities as adjuvants and antigen carriers make OMVs an appealing avenue for next-generation vaccine development strategies4,5. Vaccine adjuvants enhance the immune response to a given antigen and thus create stronger and longer-term protection against future exposure. As adjuvants, OMVs can stimulate both humoral (B-cell/antibody) and cellular (T cell) responses, strengthening their efficacy6. Simultaneously, OMVs can be engineered or loaded to display specific antigens, allowing immunisation against different diseases, including those caused by viruses. For example, OMVs displaying SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been investigated as a COVID-19 vaccine solution7,8.

Vaccination against viruses doesn’t just protect against acute viral illness but also has a role in combating bacterial antibiotic resistance, through reducing secondary bacterial infections and consequently antibiotic use9.

And why stop at infectious diseases? The vaccine potential of BEVs can be extended to other illnesses, such as cancer. Neoantigens are proteins specific to tumours, created by the mutations that accumulate in a cancer cell’s DNA. By modifying BEV surface proteins to display tumour neoantigens, BEVs could train the immune system to recognise and attack cancer cells, thereby suppressing tumour growth. Innovative use of ‘plug-and-display’ engineering systems could allow different neoantigens, or even combinations of neoantigens, to be rapidly loaded onto OMVs, paving the way for personalised cancer vaccines10.

Beyond vaccination: a broader role for BEVs in medicine?

The fundamental purpose of BEVs is to travel away from bacterial cells, carrying molecules to, or collecting molecules from, distant sites. Whether they are transferring toxins to host cells or picking up essential nutrients, BEVs are essentially a parcel delivery service. So, can we use them to deliver drugs rather than virulence factors?

Doxorubicin is an anti-cancer drug that works by damaging DNA and triggering cell death. Unfortunately, it doesn’t just kill cancer cells. Severe side effects, including cardiotoxicity, are dose-limiting and have earned doxorubicin the nickname ‘the Red Devil’. Packaging doxorubicin into liposomes has been shown to alter its half-life in the circulation, its distribution, and accumulation in tissues, ultimately reducing cardiotoxicity11. There is ongoing interest as to whether other systems for doxorubicin delivery could further optimise targeting of cancer cells, while minimising side effects12 and OMVs are one prime candidate. Mouse models of non-small-cell lung cancer have shown that doxorubicin loaded OMVs have significant anti-tumour activity, accumulate in the tumour rather than other tissues and result in lower levels of cardiac damage markers than free doxorubicin13.

Using BEVs as delivery vehicles doesn’t just have potential for therapeutic applications—they can also be used in diagnostics. For example, OMVs loaded with melanin or cationic dyes can deliver these agents to tumours, increasing contrast for optoacoustic imaging14,15. BEVs also have potential diagnostic value as a biomarker of colorectal cancer, as they reflect changes in the microbiome that are associated with the disease16.

While the medical use of BEVs is still in its infancy, this early evidence suggests that their therapeutic and diagnostic potential may extend far beyond infectious disease, with many applications yet to be uncovered.

If you are interested in isolating or characterising BEVs, our qEV size exclusion chromatography columns or our Exoid for nanoparticle measurements can help. Please reach out if you need more information.

Read the previous articles in our BEV series:

Getting to Know Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Heroes or Villains?

A Budding Problem: BEVs in Antibiotic Resistance