Could bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) help explain how bacteria survive, spread, and resist treatment? With an estimated 8 million deaths globally due to bacterial infections1, research into these microbes is taking a closer look. BEVs - small, membrane-bound particles released from bacteria, are thought to play a role in bacterial survival, pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation. These roles make BEVs prime candidates for research and, perhaps, targets for pharmaceutical intervention.

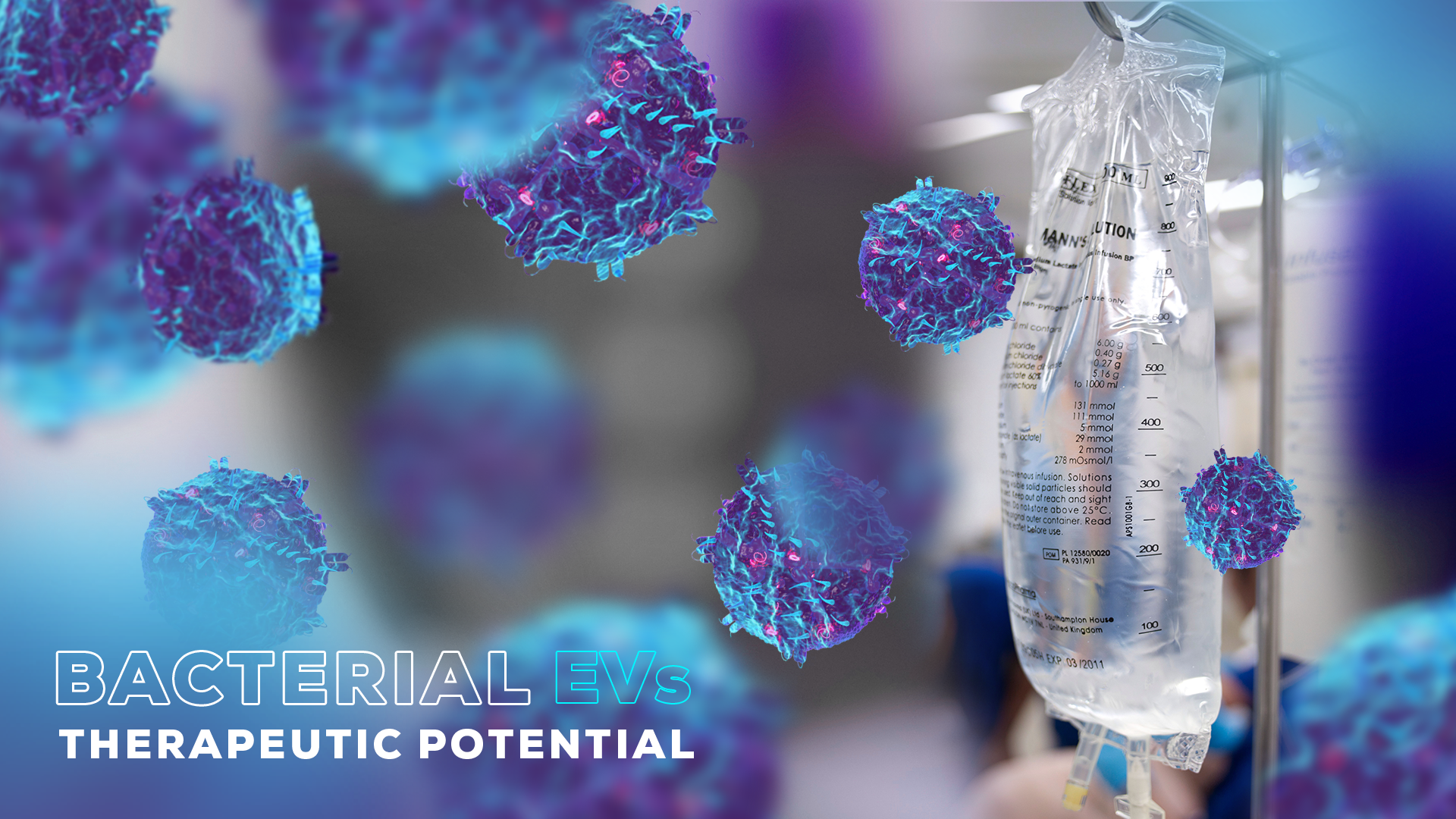

Yet not all BEVs are harmful. Some play critical roles in regulating the gut barrier and maintaining its microbiome2. Other studies suggest that BEVs could be harnessed as delivery vehicles for vaccines and therapeutics, with applications ranging from inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease to cancer3,4.

Understanding BEVs’ dual nature raises key questions for research: how can we mitigate their role in infection, and how might we exploit their properties for broader health applications?

BEV basics: from structure to function

BEV production appears to be universal, despite significant differences in cell structure between bacterial groups that lead to different biogenesis mechanisms. Gram-positive bacteria have a plasma membrane surrounded by a thick peptidoglycan wall, while gram-negative bacteria have an inner and outer membrane with a thin peptidoglycan layer sandwiched in-between (Figure 1). In addition to these structural differences, there are two methods of BEV formation: cell lysis and budding. This combination results in major differences in the structure and contents of BEVs, with half a dozen different types being described in the literature5-7. For example, outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) bud from gram-negative bacteria and contain only periplasmic contents7, whilst explosive cell lysis produces BEVs that contain inner membrane and cytoplasmic components5. Overall, there is huge heterogeneity in the quantity, size, composition and cargo of BEVs both within and between species8,9.

Unsurprisingly for such a diverse group, BEVs carry out a wide range of different functions. They remove misfolded proteins9, assist with nutrient acquisition10, facilitate communication with other bacteria11 and even enable communication with other kingdoms of life12. These activities contribute to some of the most harmful effects of bacterial infections, such as protecting and delivering toxins to host cells10. Yet BEVs also provide benefits, including supporting the symbiotic relationship between humans and our gut microbiomes2.

There are multiple facets of BEVs that make them good candidates for exploitation in therapeutic applications. They are immunogenic but not infectious, are easily produced in a lab, and are relatively easy to modify to present different antigens for vaccines. For example, a hypervesiculating E. coli strain has been engineered with endogenous proteins deleted to make way for higher loading of exogenous antigen, creating a vaccine platform potentially suitable for industrial production13. But perhaps the most extraordinary therapeutic use of BEVs could be as a living biotherapy, where oral administration of engineered bacteria results in therapeutic OMV production in the gut14.

Emerging trends in BEV research: from function to translation

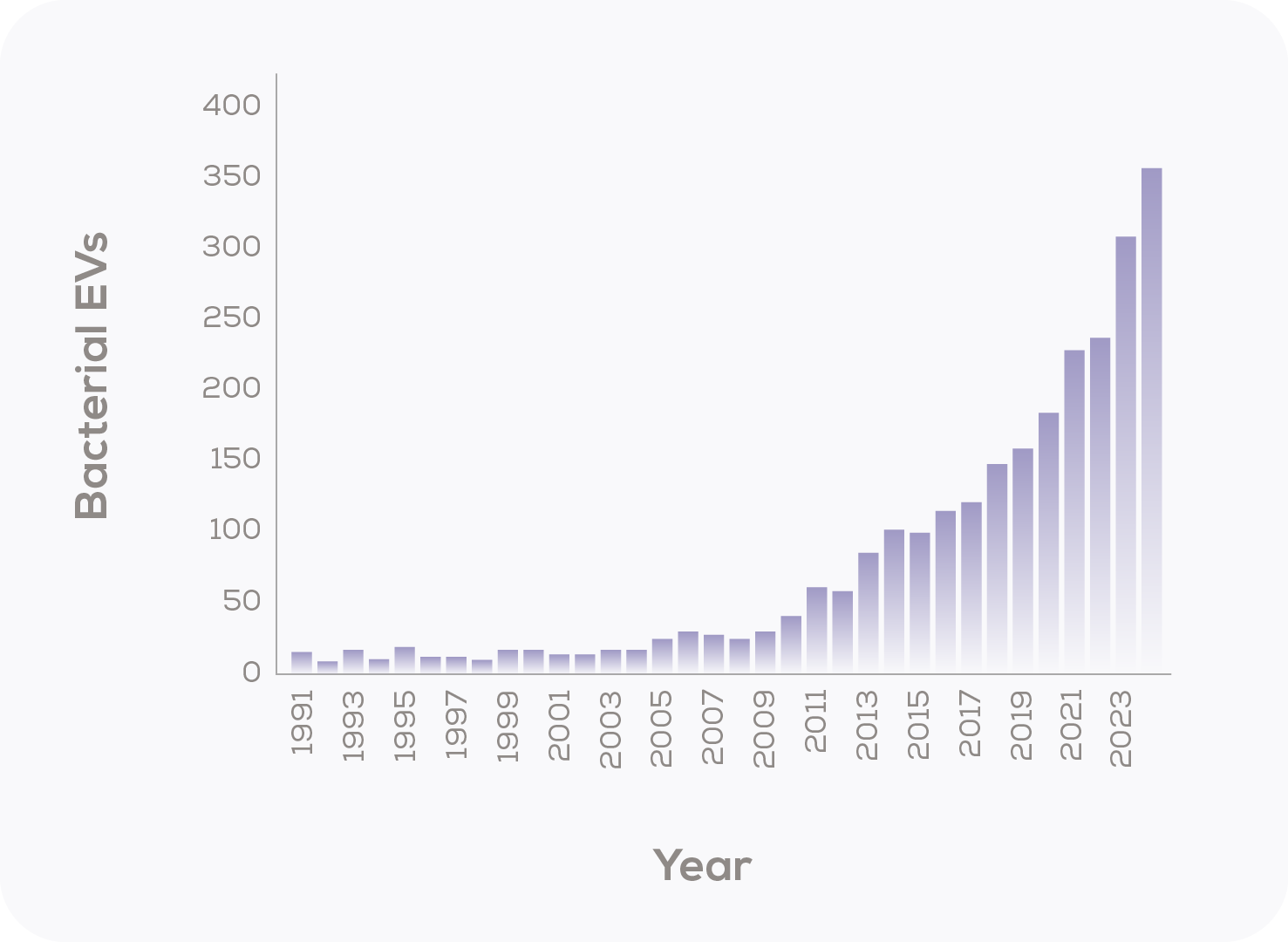

Just like many other areas of EV research, interest in BEVs is growing (Figure 2), a trend that holds even when the overall increase in published papers is accounted for. So, what are the hot topics in BEV research? A recent analysis of literature published on BEVs between 2015-2021 found that the most common aim was to understand BEV function (65%) and by far the most common analyte was BEVs from lab-grown bacterial cultures (94%)15, consistent with a field at the discovery stage. However, the translational potential of this BEV research was impressive, with nearly 20% (167/845) of studies looking at BEVs as a potential vaccine component or therapeutic15. A shift in keyword usage for BEV publications towards applied research terminology, with ‘vaccine’, ‘biomarker’ and ‘drug delivery’ increasingly used16 confirms an emphasis on translating BEV research into real-world applications and, ultimately, improved healthcare outcomes. The best BEV research, it seems, is yet to come.

Want to learn more about BEVs?

Stay tuned over the next few weeks, as we’ll be releasing a series of articles on key areas of BEV research. Next up: the role of BEVs in antimicrobial resistance. Sign up to our EV newsletter at the bottom of this page to be notified, or take a look at a previous article employing qEV and TRPS technologies to study BEVs: Exploring EVs from a Hospital-Derived Bacterial Pathogen With the Exoid and qEV10