In many parts of the world, we often take for granted that if we get an infection, a quick trip to the doctor and a few days of antibiotics will fix us. But it’s not that long since a simple infected cut could be debilitating, or even life-threatening. And before the advent of antibiotics and antiseptics, the outcomes from more severe injuries were frankly dismal. In the century before antibiotics, mortality from limb amputation was nearly 50%, with the commonest cause of death being sepsis1. Thankfully with modern medicine, those days are behind us. Or are they?

The Rise - and Impending Fall - of Antibiotics

The discovery of antibiotics in the early 1900s, and their golden age of development through the mid-20th century, increased life expectancy and enabled other major medical advancements, such as transplant surgery2. Now however, we are in danger of losing this progress as antimicrobial resistance, including antibiotic resistance, becomes a major public health concern. Without action, by 2050 infectious diseases are projected to once again become the leading cause of death, a scenario more fitting for the nineteenth century than the twenty-first3.

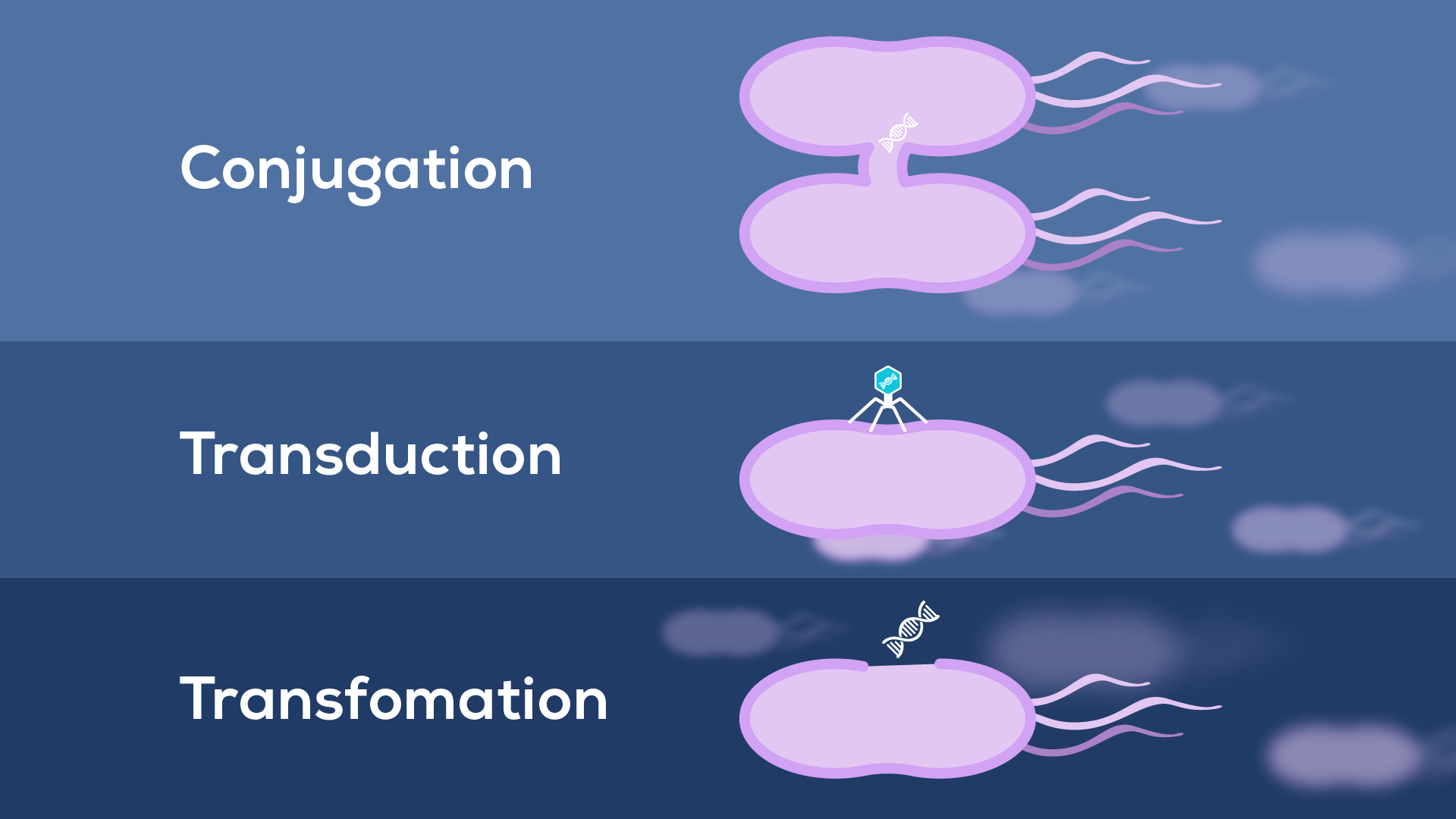

While the root cause of antibiotic resistance is the overuse and incorrect use of antibiotics, BEVs can contribute to the mechanisms by which this resistance arises. The canonical way bacteria overcome treatment is through resistance genes, often carried on plasmids and transferred between bacteria, allowing rapid acquisition and spread of resistant phenotypes4. Until recently, only three mechanisms for resistance gene transfer were known (Figure 1):

1) conjugation between bacterial cells;

2) transduction by phages;

3) transformation by environmental DNA

However, BEVs (particularly those produced by cell lysis) can contain DNA, making them candidates for a previously unrecognised mechanism of transformation. Interestingly, EVs have been shown capable of transferring antibiotic resistance, both within and between species5. Still, how widespread and effective this route is compared to other horizontal gene transfer mechanisms is currently unresolved6.

BEVs as Agents of Antibiotic Resistance

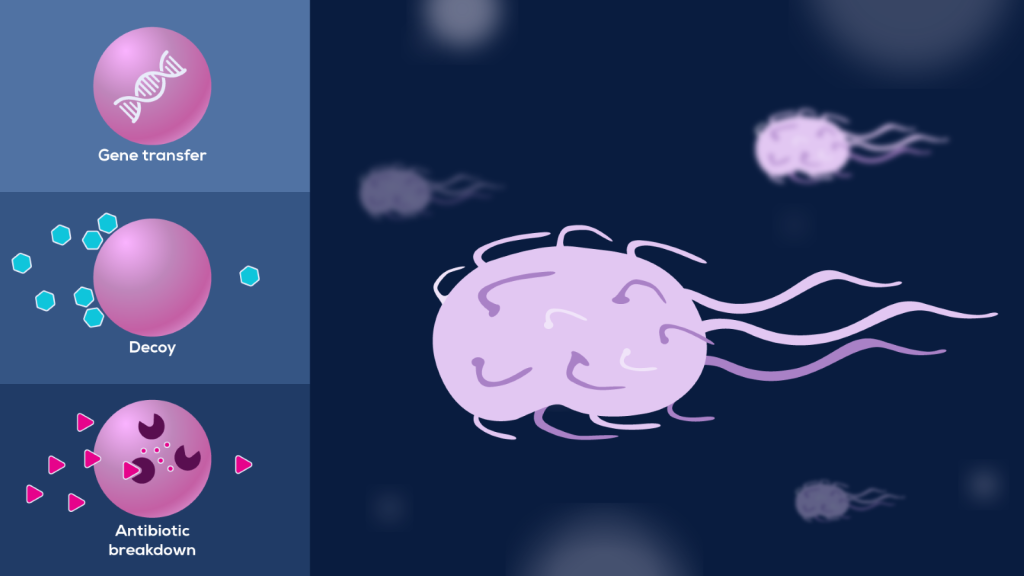

BEVs are known to support bacterial survival against antibiotics in several ways (Figure 2). For example, β-lactam antibiotic challenge of Staphylococcus aureus, a common gram-positive bacterium that can cause anything from mild skin infections to fatal septicaemia, can increase BEV production by weakening the peptidoglycan cell wall. Once released, these BEVs protect against both membrane-targeting antibiotics and the innate immune response7. This non-specific effect suggests BEVs act as decoys, mopping up membrane-targeting factors before they can bind and damage the membranes of living bacteria.

BEVs can also provide specific mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, with many bacterial species packaging β-lactamase enzymes into BEVs (Figure 2). These enzymes break down β-lactam antibiotics, such as amoxicillin. By surrounding themselves with BEVs carrying these enzymes, bacteria ensure the antibiotic is inactivated before it can exert its effect8.

Both decoy and antibiotic breakdown reduce the effective antibiotic concentration, lowering the dose bacteria are exposed to. This initial mitigation buys the bacteria time to adapt to their new environment through the acquisition of permanent resistance as described above9.

BEVs in Bacterial Biofilms

While we might be most familiar with bacteria as planktonic cultures in laboratory flasks, their most common state in nature is within biofilms. Alongside acquisition of drug resistance, biofilm formation is a key challenge in the evolutionary arms race against bacterial pathogens. Biofilms are bacterial communities, attached to a surface and protected by a secreted matrix of polysaccharides, nucleic acids, proteins and BEVs10, 11. They can form and persist on everything from hospital sinks to joint replacement implants12, 13.

Biofilms form through a stepwise process10, with BEVs appearing to play a role at several stages. They can:

- Increase bacterial hydrophobicity, promoting initial bacterial aggregation and attachment to a surface14, 15.

- Associate with matrix proteins, supporting the assembly and maintenance of the biofilm structure16.

- Carry enzymes to break down the matrix of mature biofilms and release bacterial cells back into the environment to colonise new sites17.

Because of their structure, biofilms are relatively resistant to cleaning and treatment compared to free bacteria. They create a reservoir of pathogens, often including drug-resistant bacteria, that continually spread into the surrounding environment10, 12.

Novel Approaches to Treating Bacterial Infections

The alarming ability of bacteria to rapidly evolve resistance to antibiotics means new therapeutic strategies are needed. One possibility for combating resistance is to develop novel antibiotic delivery approaches – and BEVs might just pave a way.

For example, treatment of the gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa with the antibiotic gentamicin increases BEV release. Since gentamicin enters the bacterial cells, it is packaged into these BEVs, alongside a hydrolytic enzyme. When added to bacterial cultures, these loaded BEVs cause cell lysis and even overcome resistance caused by membrane impermeability – presumably because BEVs fuse with the target cells and release their antibiotic cargo directly into the periplasm18. This is just one of many avenues being explored to leverage BEVs in nanomedicine. So, while BEVs may contribute to the rise of antibiotic resistance, they may also hold potential for the solution.

Next time, we dig further into the therapeutic potential of BEVs, including their role in vaccines and as drug nanocarriers. Sign up to our Newsletter below if you would like to get updates about BEVs or other topics of interest.

Read the previous article in our BEV series: Getting to Know Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Heroes or Villains?