These days we’re used to thinking about viral variants, but did you know that mutations that give rise to new strains of the flu or COVID-19 are just the tip of the iceberg? Many viruses have a high replication error rate, generating heterogenous populations with diverse genomic mutations and structural alterations. While most of these won’t give rise to the next wave of a pandemic, that doesn’t mean they are irrelevant. In this article we explore one particular subtype of viral particle – the defective interfering particle, or DIP.

What actually are defective interfering particles?

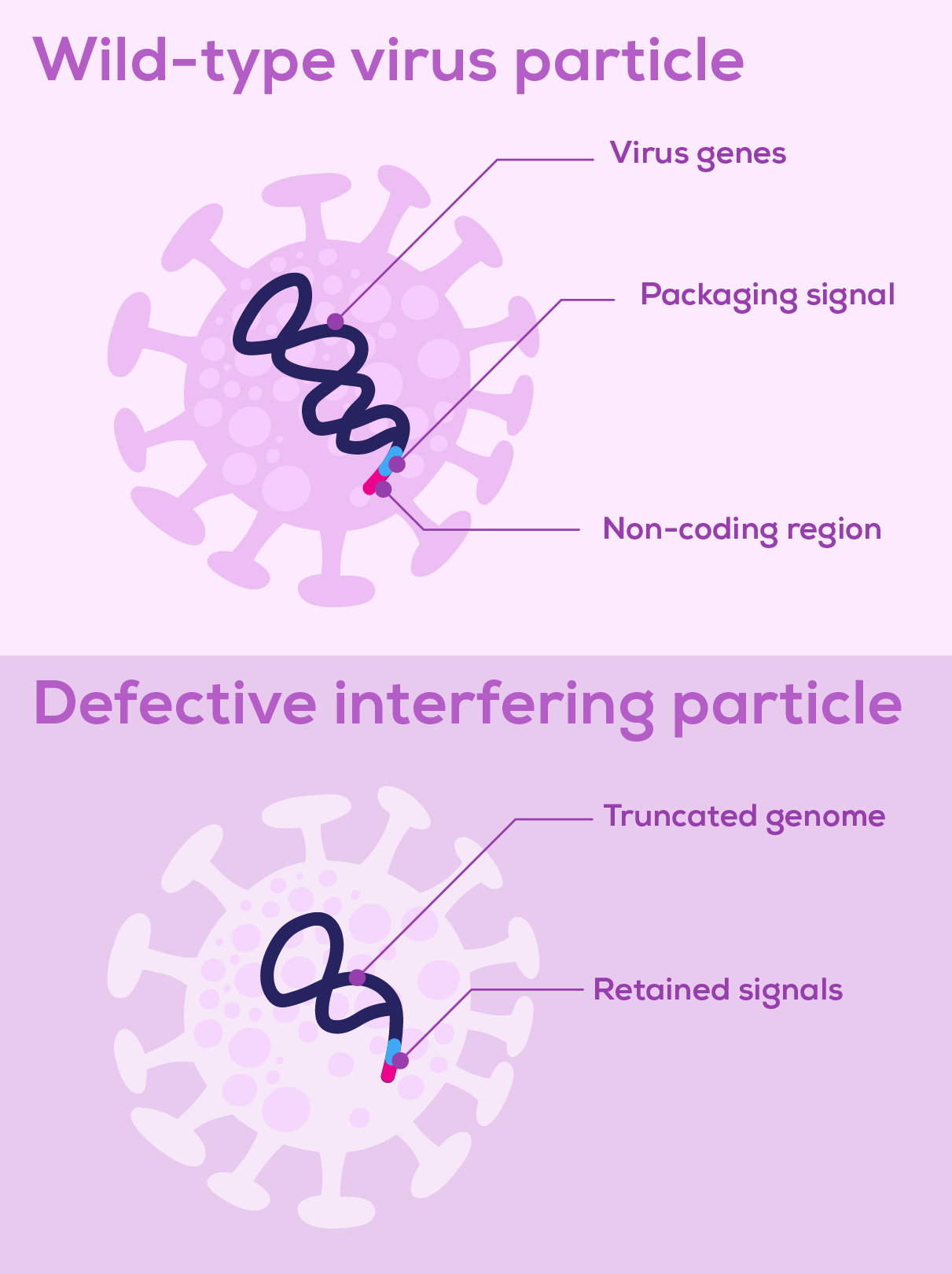

Defective interfering particles (DIPs) are virus particles consisting of a defective viral genome (DVG) packaged in a normal viral particle (Figure 1). These defective viral genomes arise spontaneously due to replication errors deleting, rearranging or mutating the virus’ genetic material. Such genetic alterations make DVGs unable to replicate by themselves. However, if the DVG genome retains the signals that initiate replication and enable packaging, DVGs can be replicated and assembled into viral particles in cells coinfected with wild-type virus, which supplies the missing proteins and functions1,2. Some DVGs are faster to replicate than the wild-type viral genome, competing for viral replication and encapsidation machinery and outproducing wild-type virus particles3. It is this interference of wild-type virus replication by defective particles that gives DIPs their name.

Why should we care about DIPs?

Whether DIPs represent a challenge or an opportunity depends on the context. On one hand, their ability to inhibit viral replication gives them the potential to serve as antiviral therapeutics. On the other, this quality could be a drawback, as they may hamper the large-scale production of viruses for applications such as vaccines.

The discovery of defective interfering particles

The emergence of DIPs was first reported in the late 1940s by Preben von Magnus (although they were not termed DIPs until much later). Von Magnus identified defective virus particles appearing during serial inoculation of eggs with influenza virus4. Decades of research followed, finding the ‘von Magnus phenomenon’ in virtually all virus families1,2,5, during both natural infection and in vitro6,7. The dynamics of DIP outgrowth were shown to be dependent on the multiplicity of infection (MoI), with higher doses causing earlier emergence of interference, cyclical expansion then reduction of the wild-type and DIP virus populations, and disruption of virus production with lower yields1,6,8. These discoveries—that DIP development is widespread during virus replication and can impact virus growth dynamics—establish DIPs as an important consideration when establishing in vitro viral production systems.

The challenge of DIPs in vaccine manufacturing

The DIP effect poses significant challenges for vaccine manufacturing. Flu vaccines are conventionally produced from viruses grown in chicken eggs. However, inoculating and harvesting millions of eggs each year is laborious. Moving to cell culture-based vaccine production can offer advantages for practicality, scalability and production speed, all beneficial features in the face of future pandemics9. Continuous viral culture is considered a particularly desirable approach because it maximises the use of production equipment and optimises cost efficiency10. Initial attempts at continuous culture production of flu virus were characterised by oscillating viral titres due to DIPs7. While there have been attempts to overcome this with method optimisation11, cell culture-based vaccine manufacturing continues to largely rely on batch production12, and egg-based manufacturing continues to dominate flu vaccine production13.

DIPs as obstacles to new therapeutic opportunities

It's not just vaccination production that can be negatively affected by DIPs. Efforts to develop baculoviruses as bioinsecticides have been hampered by DIPs, necessitating efforts to modify viral genomes and suppress the formation of DVGs14. Perhaps more significantly, baculoviruses are widely used for recombinant protein production and are increasingly of interest for virus-like particle vaccine production and gene therapy15,16. DIPs hamper these applications as well, with the potential to impact both product quantity and quality17,18. Strategies are required to manage and reduce these effects and hence constrain process development19,20.

Using tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) for viral particle analysis

Despite their ubiquity and potential impacts on manufacturing processes, challenges in DIP detection persist. DIPs are generally indistinguishable from wild-type virus when analysed using techniques based on particle characteristics such as size, density or morphology21. The variety of structural and sequence changes present in DIPs means that PCR-based methods may miss some subpopulations22, 23. Truly unbiased DVG detection necessitates sequence-agnostic techniques such as next-generation sequencing, although this tends to be both more expensive and more complex to analyse than quantitative PCR approaches22. Plaque assays measure infectious particles and therefore cannot detect DIPs directly. Intriguingly they can qualitatively indicate the presence of DIPs—an absence of plaques at high virus concentrations but presence at lower concentrations suggests DIP interference that is titrated out24.

Because of the difficulties of direct, quantitative DIP detection, a combination of techniques is needed to work out firstly the total number of viral particles, and secondly the proportion that are infectious. Tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) is a long-established method for counting virus particles25,26. Recently it has been used, alongside plaque assays, to check DIP levels in a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine production system using stirred-tank bioreactors27. The total number of virus particles was determined by TRPS, while plaque assays were used to calculate the number of infectious particles. In this way, the ratio of infectious to non-infectious particles could be compared across manufacturing methods, demonstrating that DIP levels were not significantly different between a plate-based method and the stirred-tank bioreactor method27.

Learn more about single-particle analysis with TRPS